Rewards can hijack dopamine and make hard tasks even harder

Everyone loves to reward themselves with something pleasurable after completing a hard task: the coffee after a long day of studying, the beer after a long day at work, the smoothie after a hard workout.

In cognitive psychology, there are two ways that we can be motivated: intrinsically, and extrinsically. Working hard on a task in pursuit of a reward or end goal would be extrinsic motivation. In contrast, working hard on something because you enjoy it and want to do it would be intrinsic motivation.

The instinct to give yourself a carrot as a source of motivation may actually hijack our brains internal mechanisms of self-motivation. When we receive an award after completing a task, we tend to associate significantly less pleasure or motivation with the activity itself.

Intrinsic motivation can help you not just endure, but enjoy the hard work when completing a challenging task. Pushing through for an end goal or reward isn’t bad, but you will often end up rushing through the task itself, and being utterly miserable in the process.

Intrinsic versus Extrinsic Motivation

Extrinsic motivation can be important in motivating people to do necessary, but unpleasant tasks. Maybe you absolutely HATE cleaning, but you still need your house to be livable. A nice meal after a hard day of cleaning can help sweeten the deal, and associate the act of cleaning, something you hate, with something pleasurable.

Intrinsic motivation is, however, a more powerful form of motivation. When you enjoy a task, you have intrinsic motivation to do it. If you enjoy running, then you have an intrinsic motivator for going for a run, while someone who hates running may need a reward or end goal to get to go jogging.

Intrinsic motivation comes from a desire to seek out novel experiences and challenges, and to utilize one’s potential with a drive to explore and learn. Self determination theory has somewhat-recently emerged as the prevailing framework for studying intrinsic motivation.

Working hard at your job for a paycheck or positive performance review is also an example of extrinsic motivation. Not everyone gets the privilege of loving their job, so these extrinsic motivators are helpful if not essential for many. Getting praise for your hard work, which is an extrinsic motivator, can also help you build your intrinsic motivation for a given task.

However, for activities that you do enjoy, or want to enjoy, adding extrinsic sources of motivation can actually weaken your intrinsic motivation. This makes a once pleasurable or potentially pleasurable task feel like work and less enjoyable in the moment.

Effects of Extrinsic Rewards on Intrinsic Motivation

A 1974 study at Stanford by David Greene and Mark Lepper explored how providing an external reward affects intrinsic motivation for an enjoyable activity. The study focused on preschool-age children who enjoyed drawing.

In the study, children who had previously expressed an enjoyment of drawing were assigned to one of three groups. One group was told that they would receive an award for completing a drawing. The second group were not told about the reward, but received one when they completed the drawing. The third group received no reward but still did a drawing.

One to two weeks after this experimental session, the children were observed again to assess their intrinsic motivation for drawing. Those in the reward conditions showed decreased internal motivation for drawing, while those in the no-reward condition did not show any change in their intrinsic motivation for drawing.

This study added to a growing body of evidence for the power of intrinsic motivation, and the potential for extrinsic rewards to affect it negatively.

Dopamine: The Neurotransmitter of Wanting

Dopamine is often thought of as the “reward” neurotransmitter. It is true that dopamine is critical to our brains’ reward pathways, both for natural and drug induced neurochemical rewards. However, dopamine is actually not responsible for the pleasurable feeling of a reward– it is responsible for the feeling of craving or wanting that reward.

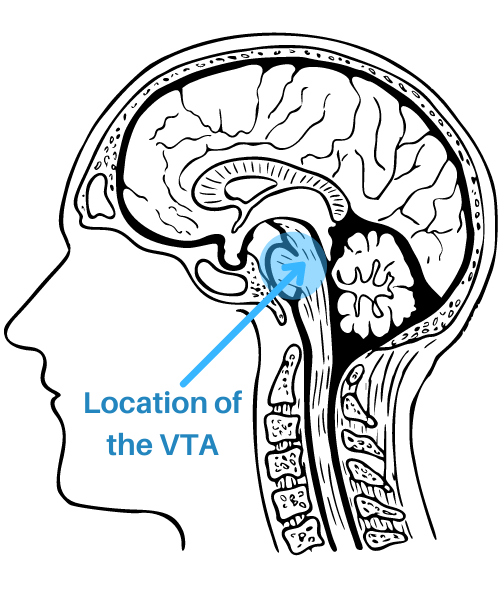

The ventral tegmental area (VTA) is a crucial part of the reward pathways. The VTA is a group of neurons in the midbrain that largely controls reward cognition: motivational salience, associative learning, and positive emotions.

Associative learning allows us to associate a behavior or context with a specific outcome. For example, many of us associate the act of going to work with the outcome of getting a paycheck. We also associate getting a paycheck with positive emotions.

The VTA is rich in dopaminergic neurons, or neurons that release dopamine. Dopamine can be released from neurons in one of two independent mechanisms: phasic release and tonic release.

Phasic Dopamine Release

Phasic dopamine release refers to spikes of dopamine release that occur when dopaminergic neurons fire. This occurs in reaction to a specific event, like receiving a reward. A “reward” in terms of neuroscience can be anything that triggers a phasic release of dopamine.

Many drugs (including nicotine) trigger a phasic release of dopamine, but so do tasty foods, sex, and positive reinforcement from others. Eating chocolate leads to a spike or release of dopamine, as does receiving praise from a friend, family member or coworker.

A phasic release of dopamine feels very good at the moment, but dopamine levels very quickly return to baseline, or often below baseline, following the initial spike.

Dopamine Detox

The initial spike does not last very long, and depending on the type of event that triggered the release, dopamine levels may take some time to even return to baseline following a spike. Many addictive drugs lead to a large spike in dopamine followed by a drop to well below baseline, contributing to the crash that often follows a high.

Frequent engagement in activities that spike dopamine levels can lead to a decrease in baseline dopamine in the long run.

ADHD is often characterized by lower than normal levels of dopamine in the brain, and symptoms typically include poor motivation, difficulty focusing and difficulty sustaining attention on tasks. Many people now report experiencing symptoms of ADHD despite not having a clinical diagnosis.

Many experts believe this may be connected to the frequent spikes in dopamine associated with heavy smartphone or social media use, which has become almost universal.

The idea of a “dopamine detox” has been increasing in popularity, and challenges one to abstain from all activities that lead to these spikes in dopamine: sugary foods, video games, social media, etc. Some believe that a “dopamine detox” can help increase one’s baseline levels of dopamine, leading to better focus and motivation.

Tonic Dopamine Release

Tonic dopamine release establishes your baseline levels of dopamine, and is regulated by afferent (bring information from sensory organs towards the brain) neurons in the prefrontal cortex.

This type of dopamine release is responsible for our general motivation levels– how excited or motivated we are to pursue a goal at any given moment.

Behavioral patterns (and nutrition!) can have a big impact on our tonic release of dopamine. Frequent dopamine spikes, or phasic release, can downregulate our tonic dopamine release.

Having a sufficient baseline dopamine level is essential to working efficiently towards our goals, whatever those goals might be. Dopamine is associated with positive affect, cognitive flexibility and creativity. Not only does tonic dopamine release allow you to enjoy the process of exerting effort, it also will make your effort a lot better.

Enjoy the Process

When you are working hard towards a long term goal, it is always tempting to provide yourself smaller rewards on the way, in an effort to maintain motivation. However, research suggests that this is likely to hurt your efforts and your motivation in the long term.

To enjoy the process, you want to focus more on achieving a solid baseline of tonic dopamine release, and less on providing yourself with regular spikes of phasic dopamine release.

A soft “dopamine detox” may help you achieve a higher dopamine baseline, which would definitely help in achieving intrinsic motivation in working towards your goals. It is also helpful to avoid dopamine stacking, or engaging in multiple dopamine spiking activities all at once, creating an extremely high dopamine event.

The biggest takeaway is to work on turning the effort into the reward– if you can even trick yourself into enjoying the process, it will feel more rewarding and more enjoyable overall.

This article was inspired by Episode 39 of the Huberman Lab podcast, “Controlling Your Dopamine for Motivation, Focus and Satisfaction.” I recommend checking out this episode for more information about dopamine, motivation, and turning the effort into the reward.

Read More

Beeler, J. A., Daw, N., Frazier, C. R., & Zhuang, X. (2010). Tonic dopamine modulates exploitation of reward learning. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2010.00170

Di Domenico, S. I., & Ryan, R. M. (2017). The emerging neuroscience of Intrinsic Motivation: A new frontier in self-determination research. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2017.00145

Greene, D., & Lepper, M. R. (1974). Effects of extrinsic rewards on children’s subsequent intrinsic interest. Child Development, 45(4), 1141. https://doi.org/10.2307/1128110